Author: Aditya Bose

Correspondence: aditbose@researchlogic.org

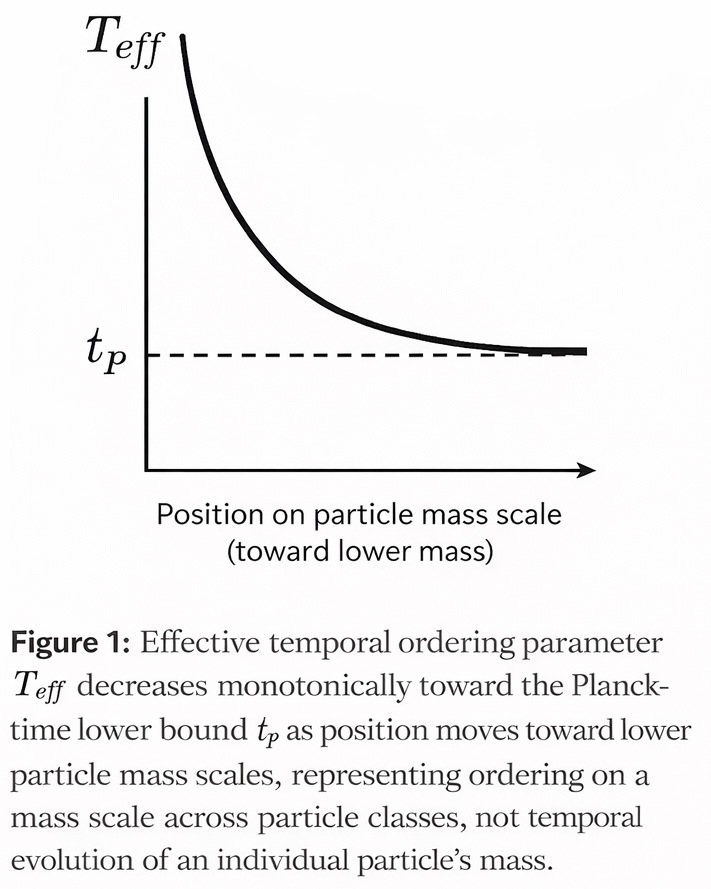

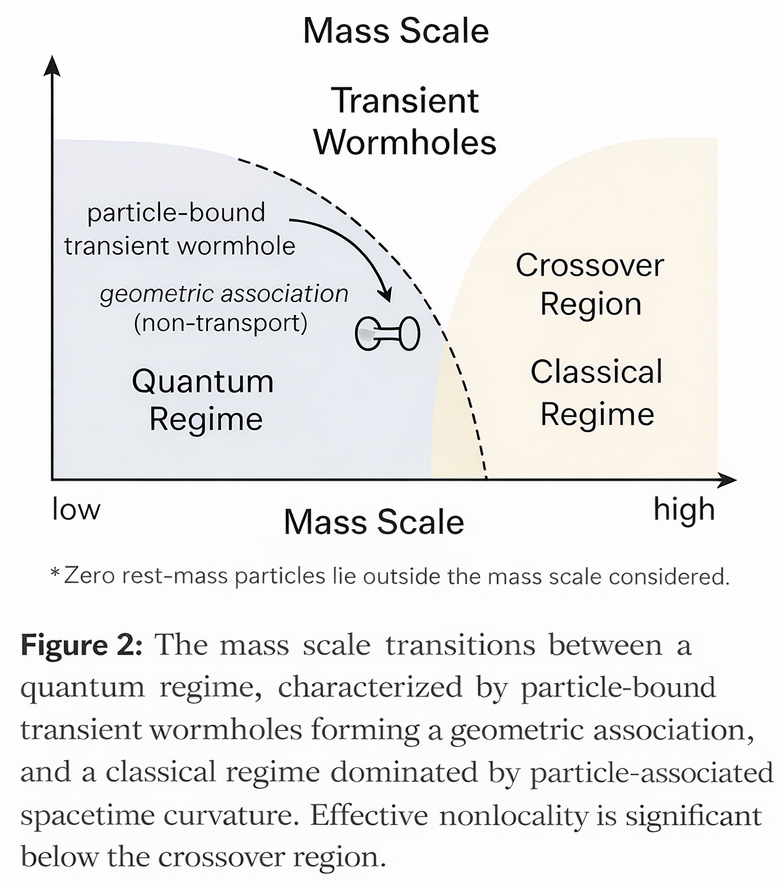

The influence of particle-associated spacetime curvature on particle dynamics weakens at smaller particle mass scales, leading to an acceleration of effective state evolution characterized by Teff, which is taken to be bounded by the Planck time as a theoretical lower limit within this framework. At sufficiently low masses, the effect of particle-bound transient wormholes becomes significant, offering a geometric interpretation of quantum nonlocality, preventing further meaningful subdivision of particles.

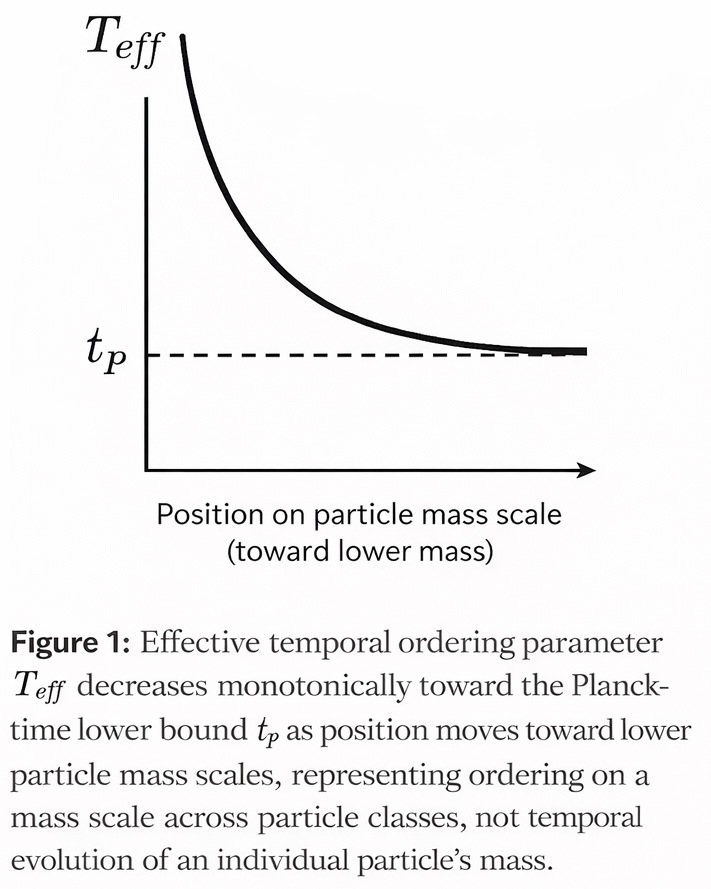

Wormhole influence increases as particle mass decreases, while classical particle-associated curvature increases with mass, representing complementary aspects of the same physical transition, with a crossover region determining which influence dominates. For particles with masses below this region, particle-bound transient wormhole effects emerge progressively and the influence of particle-associated curvature is correspondingly subdued; above the region, the reverse holds, with curvature becoming dominant and wormhole effects diminishing.

In standard quantum physics, the behavior of electrons and similar particles is described using wavefunction, a mathematical tool that tells the probability of finding a particle at different locations and explains many observed effects, such as interference patterns, atomic energy levels, and measurement outcomes. However, it does not explain why a particle behaves in a spatially nonlocal way, nor does it describe any physical or geometric mechanism underlying this behavior. It simply provides a successful rule for prediction.

The present work does not attempt to replace the wavefunction or modify the established equations of quantum mechanics. Instead, it offers a complementary, phenomenological interpretation. In this view, effective nonlocal behavior is associated with transient, particle-bound wormhole structures that remain coupled to individual particles. These wormholes are not treated as physical tunnels or transport channels, and they do not alter quantum evolution. Rather, they provide a geometric way of interpreting mass-dependent nonlocal behavior, while the wavefunction continues to serve as the correct mathematical description of quantum states.

Conceptual discussions of short-lived, quantum-scale spacetime connections have appeared intermittently in earlier phenomenological studies. The present work advances this idea by organizing the interplay between particle mass along a single mass scale, spacetime curvature, and transient wormhole geometry, incorporating Planck-time constraints and introducing a crossover region that governs the transition between curvature-dominated and wormhole-influenced regimes.

The wormholes in this work are treated as phenomenologically defined, particle-bound geometric structures that become effective at quantum scales where classical curvature ceases to be a reliable geometric descriptor. The approach applies to particles whose positions lie on the lower side of the mass scale, below the crossover region, where effective locality weakens and quantum-scale delocalization becomes significant.

Above the crossover region, with increasing position on the mass scale, the effects of wormholes on particles gradually weaken, while the effects of curvature on particles gradually strengthen.

Within this framework, particle-bound wormhole structures are defined only for particles with nonzero rest mass; particles with zero rest mass are excluded, as discussed further in Section 4.2.

At sufficiently large particle masses, where particle-associated spacetime curvature is significant, temporal behavior is well described by general relativity, and particle-bound wormhole effects are negligible.

In this regime, stability corresponds to an object's position on the mass scale: objects lying higher on the mass scale are inherently more stable, provided the object is not subject to intrinsic or externally induced motion.

In addition, the effective ordering parameter Teff is assumed to be inversely proportional to the classical curvature scale, meaning that stronger curvature slows the effective ordering of particle states relative to an external reference.

At smaller particle mass scales, the influence of particle-associated spacetime curvature weakens. In this regime, the effective ordering parameter, Teff, increases, bounded by the Planck time. The particle begins to exhibit effective nonlocal behavior, which may be interpreted geometrically in terms of transient, particle-bound wormhole effects.

This framework presents the particle-bound wormhole association as universal in an interpretive sense—applying, in principle, to all particles and physical systems—analogous to the way spacetime curvature is associated with mass-bearing entities. However, the effects of this association become significant only below the crossover region. At this domain, these wormholes give rise to effective nonlocal behavior of particles and contribute to a relative stabilization against further subdivision below a minimum effective scale, without altering the standard framework of quantum state evolution.

These particle-bound quantum wormholes are not physical conduits for matter or information transfer, as discussed further in Section 5.

When classical curvature and wormhole influence become comparable for a given particle, classical locality begins to lose descriptive adequacy, marking the crossover region. This is not a sharp boundary but a transition zone: particles on the lower side tend to be governed by wormhole effects, while those on the higher side remain curvature-dominated. The crossover region lies deeper on the quantum side than on the macroscopic side — starting from the crossover region on the particle mass scale and moving toward smaller mass scales, wormhole effects gradually become significant. In contrast, above the crossover, wormhole effects gradually diminish, as classical curvature dominates in accordance with the particle or object mass toward higher mass scales.

The influence of wormholes on quantum particles of different masses is discussed in detail in Section 4.

In the deeper quantum regime, where wormhole effects exert a stronger influence than classical curvature, a particle-bound wormhole may either remain continuously co-located with that particle, with its effective geometric orientation adjusting in response to the particle’s evolving state, or manifest through transient wormhole configurations that re-establish the association across successive particle states. Together, these behaviors give rise to effective nonlocality associated with the particle, without altering the underlying quantum state evolution.

In the present work, the minimum stable particle mass arises from increasingly rapid particle repositioning due to particle-bound wormhole effects, which become progressively more significant at smaller particle mass scales. Accordingly, within this regime, particles at progressively smaller mass scales exhibit increasing stability against further subdivision due to more effective nonlocal repositioning.

As discussed in Section 2.2, the rate of effective state evolution is ultimately limited by the Planck time. This bound constrains sequences of particle state changes or repositioning events from occurring arbitrarily fast, preventing scenarios in which evolution would appear instantaneous or lose a well-defined classical interpretation. Together, the Planck time, the emergence of a minimum stable particle mass, and the maximal effective influence of particle-bound wormhole behavior define the smallest physically meaningful scales within this phenomenological framework.

Experiments show that quantum particles lying on the low-mass scale, such as electrons, can occupy spatially delocalized states rather than a single definite position.

Particles with still smaller masses on this scale, such as neutrinos, lie deeper into the wormhole-dominated regime, with potentially higher rates of repositioning and effective Teff, reflecting faster delocalization.

Electrons and neutrinos are introduced here as illustrative examples that justify, by application, the framework developed in Section 3.1.

Photons do not admit particle-bound wormhole structures within this framework, because they lack effective curvature on the mass scale due to their zero rest mass; consequently, wormhole-mediated nonlocality is inapplicable to them.

For particles and systems occupying positions above the crossover region on the particle mass scale, the framework remains applicable, but describes that wormhole influence is progressively suppressed as curvature effects become increasingly effective. This category includes the following systems:

A. Hadrons and Nuclei

B. Larger Composite Systems

whose effective behavior is also governed by classical curvature.

Finally, at the level of constituent particles within hadrons, such as quarks and gluons, the situation is different in principle. While their effective mass scales would place them below the crossover region, these constituents never appear as isolated particles and remain permanently confined within hadrons. Consequently, the framework cannot attribute observable repositioning or wormhole effects to them. Any discussion of constituent-level behavior therefore remains entirely conceptual and lies outside the scope of the present work.

No modifications to standard quantum evolution or established wave-based descriptions of quantum phenomena are assumed. The proposal is purely interpretive, providing a geometric description of effective nonlocality without altering known quantum dynamics or introducing new state-evolution equations. The wormholes are introduced purely as transient, particle-bound geometric structures operative at quantum scales, with no macroscopic manifestation or transport function. The term "wormhole" does not refer to, assume the absence of, nor seek to redefine the macroscopic, traversable structures or speculative black hole-white hole connections often discussed in astrophysics or science fiction. This work is purely phenomenological.

Particle repositioning via transient wormhole influence does not imply enhanced interaction or collision probability between particles. Wormhole effects are strictly particle-bound and operate independently for each particle, without constituting shared transport pathways, mediating forces, or correlated localization events.

This framework is distinct from recently discussed holographic wormhole proposals, which arise in a different theoretical context. The mechanisms underlying such constructions are not addressed here, and no connection is assumed. The present work concerns only mass-dependent, particle-scale transient wormhole behavior in a phenomenological sense; holographic wormholes therefore lie outside the scope of this study.

While spacetime curvature in general relativity depends on the full stress–energy tensor, this work intentionally treats particle rest mass as an effective proxy for curvature influence for phenomenological clarity.

Future work may explore how wormhole influence on particles aligns with the mass scale, including possible modulation mechanisms or alternative functional dependencies, such as logarithmic or exponential behaviors. These possibilities remain speculative, pending further investigation into the dynamics of transient quantum-scale wormholes.

This work presents a phenomenological framework aimed at conceptually interpreting particle nonlocality via transient, particle-bound wormholes. While certain physical quantities, such as mass, Planck time, and spacetime curvature, are referenced, the model is not derived from first principles in general relativity or quantum field theory. Instead, these concepts are employed as interpretive tools to construct a coherent framework for understanding effective nonlocal behavior. As such, deviations from established theories, approximations, or simplifications—such as treating mass as the primary determinant of curvature influence on single particles—are intentional and serve the purpose of phenomenological illustration rather than rigorous derivation.